- Москва, ул.Лётчика Грицевца 14а,

м. «Пыхтино» - Ежедневно, с 1200 до 2000

- +7 (915) 000-77-99 - (Телефон салона) +7 (915) 000−77−99 - (WhatsApp)+7 (915) 000−77−99 - (Viber)

- domtattoo@yandex.ru

THE TATTOOIST'S OCCUPATIONAL REWARDS

Все о татуировках

- Стили татуировки

- Белая татуировка

- Биомеханика (Biomechanics) и Органика

- Блэкворк ( Blackwork)

- Дотворк (Dotwork)

- Готика «Gothic»

- Кельтские

- Клокворк

- Нью Скул ( New School)

- Олд Скул ( Old School)

- Ориентал (Oriental)

- Полинезия

- Реализм

- Стимпанк

- Сюрреализм (Сверхреализм)

- Трайбл (Tribal)

- Треш полька

- Черно-серая "Black&grey"

- Чикано (Chicano)

- Этнический стиль тату (Ethnic)

- Японские тату

- Тотемные тату Тлинкитов

- Татуировки- надписи

- Временная татуировка.

- Хоррор

- Парные тату

- Крестиком

- Кружева

- Ультрафиолетовая татуировка

- Татуировки на частях тела

- Надписи для тату с переводом

- Надписи с переводом с немецкого на русский язык

- Надписи, афоризмы, цитаты на португальском и бразильском языке с переводом на русский

- Надписи на испанском с переводом

- Перевод фраз и гимнов (стихов) с хинди на русский

- Фразы, надписи и афоризмы на арабском языке с переводом

- Надписи для мужчин

- Надписи для мужчин с переводом

- Благородный муж

- Друзья и дружба - мысли великих.

- Труды, достижения и ошибки - надписи для тату

- Враги и недруги, война и кровь в надписях для мужчин

- Надписи о Смелости и Силе для мужских тату с переводом

- 120 надписей для Мужчин о Смелости, Силе и Движении Вперед

- Тату надписи для Мужчин-воинов и защитников Отечества на тему Смелости, Чести, Мужества, Долга и Действия

- Надписи для девушек

- Надписи на тему: Любви, Семьи и Верности с переводом на Английский

- Надписи с переводом о семье на разные азыки мира.

- Вопросы о татуировках

- Астрология и астральная геометрия

- Значение тату

- Уход за татуировкой

- Для СМИ и видео проектов

- Татуировка на шрамах

- Иглы и краски для татуировок

- Зодиакальные татуировки...

- Стили, виды татуировки. Сведение тату.

- English language

- Все о Сак Янт - Тайской Шаманской Татуировки

- Священные татуировки - ИЗ ПРОШЛОГО

- МАГИЧЕСКИЕ ЧЕРНИЛА: ЗАКЛИНАНИЯ И СИГИЛЫ

- ИГЛОЙ НА КОЖЕ

- ЛУК СИТ

- КХРУ САК

- ВИЧА

- ТЕКСТЫ И ЧИСЛА, ТЕЛЕСНЫЙ ЩИТ

- ЯНТРЫ ЧОК ЛАП ПРИНОСЯТ УДАЧУ И ПРОЦВЕТАНИЕ.

- ТРАНС

- ТРАДИЦИИ САК ЯНТ В ТАИЛАНДЕ

- ЗАКЛИНАНИЯ И ПИСЬМЕНА

- Обучение мастеров-татуировки в Тайланде (ТРАНСФОРМАЦИЯ И ДИСЦИПЛИНА)

- Сигилизм

Информация

- Портфолио

- Все о пирсинге

- Виды и стили

- Подготовка и процедура пирсинга

- Когда пирсинг уже сделан

- Бод Мод

- Украшение для пирсинга

- Инструмент для пирсинга

- Словарь терминов

- Cтоимость пирсинга

- Магическое, символическое значение пирсинга

- Вопросы и ответы про пирсинг

- Удаление татуировок

- Все о татуаже

- Новости

- Ответы на часто задаваемые вопросы о тату.

- Работы тату художника Yann Travaille

- Съемки MTV

- Проба пера

- Съемки Дискавери в судии ...

- Энциклопедия пирсинга

- 7 Московская Международная Тату Конвенция

- «Звёздный» гость салона «Дом Элит Тату» - известный продюсер Андрей Клюкин

- Ушел из жизни тату мастер Илья Смирнов

- Мы примим участие в Питерской тату конвенции 2015 года

- У нас делают татуировки модели Creepy Sweets

- Оригинальный майки и футболки с аэрографией за 4.000 рублей

- Мы получили независимую премию "Лучший Тату Салон 2015 года" по версии портала Татуировка.Рф

- Мы участники и победители тату конвенции в Москве

- Мы организаторы "Ночи Татуировщика 2015 в Москве"

- Rock heroes: Miss Тату Хабаровск

- Немецкий политик сядет в тюрьму за то что сделал нацистскую татуировку

- Международная Московская Тату Конвенция 2016

- Санкт-Петербургский Тату-Фестиваль

- 2 Международный фестиваль татуировки Сочи 2016

- Самый старый татуированный человек на нашей планете.

- 9-я Международная Московская Тату Конвенция 2017

- Тату мастер с 1.4 миллионом подписчиков маскирует растяжки

- Miss Tattoo Australia Дженн Десмонд - водитель грузовика

- Тату разрешены

- Зейн Малик сделал татуировку с глазами Джиджи Хадид на груди

- Тату как запрет на реанимацию

- В честь ЛДПР прошла тату-вечеринка

- Тату салон в Самаре

- Аренда места в тату салоне Москва. Как правильно и главное где арендава

- Обучение и все о нем

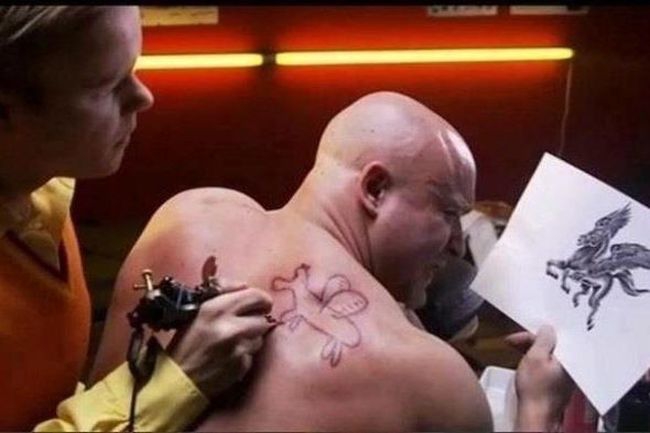

Tattooists, as we have seen, are drawn to the occupational activity by the independence, creativity, and income it offers. Depending upon the tattooist's orientation to tattooing, the occupational rewards of reliable income and creative opportunity are weighted differentially. Street tattooists define themselves as involved in a predominantly commercial enterprise that has the advantage of affording some degree of creativity. Fine art tattooists who specialize in custom designs emphasize the creative opportunities of the work but are also pleased that tattooing provides the financial security lacking in many artistic endeavors. One tattoo artist put it this way:

So tattooing suddenly appeared in my life and I realized that

there was that opportunity to do that thing I always wanted to do so badly my

entire life. That was to communicate on some indescribable level with each

indiVidual person that carne through the door. At the same time I was making

art and communicating, I was making a living…. Right from the first I deCided

I really wanted to tattoo as an alternative art form. It really gave me a

chance to explore a fresh new place. I still believe

This artist touches on a feature of the

tattooing occupation that was most commonly cited as the major ongoing reward

by experienced tattooists. InteraCting with clients, ascertaining their needs,

developing trust. fulfilling their desires, and vicariously feeling their

pleasure were rewarding. The positive social experiences contained within the

client relationship came to be defined as the dominant rewards of tattooing for

a living.

This artist touches on a feature of the

tattooing occupation that was most commonly cited as the major ongoing reward

by experienced tattooists. InteraCting with clients, ascertaining their needs,

developing trust. fulfilling their desires, and vicariously feeling their

pleasure were rewarding. The positive social experiences contained within the

client relationship came to be defined as the dominant rewards of tattooing for

a living.

As with all service occupations, the relationship with the client is of central importance in tattOOing. The client not only consumes the service/product, but also interacts with the service deliverer to shape and define the characteristics of the service outcome.

Consequently, interaction with clients is central to the

tattooist's experience

Let's assume the person is reasonably intelligent and isn't

getting the tattoo just to prove a point. Let's assume it was done when the

person was cold sober and that the person who was working on him is as

interested in making art as he is interested in making a day's pay. The

tattooist has worked with the individual to discuss the design, the placement,

the color, and then the person gets the tattoo. The first effect is the person

feels an incredible sense of accomplishment. I see it all the time. As soon as

I finish a tattoo I send the person to the mirror. I don't look at the tattoo,

I look at the guy's face. You see a smile break across the person's face. «Fuck

it. I did it. I overcame

Not all tattooees are joyful and appreciative. As discussed in

the preceding chapter, regretful tattoo clients are dissatisfied with the

technical quality of the work ancLbr the design chosen. Medical removal of

tattoos is expensive, painful, and rarely results in an entirely satisfactory

(that is, unscarred) outcome (see Goldstein et al., 1979). Other than simply

learning to live with the unsatisfactory mark, the regretful tattooee has the

alternative of having the piece covered up with another tattoo or redone by a

(one hopes) more competent artisUcraftperson. Interviewees estimated that

between forty and sixty percent of their work involved covering or redoing the

tattoos of regretful tattooees. This was the work activity that the tattooists

defined as most technically challenging and socially rewarding. In creatively

altering or obliterating the offending mark the tattooist became the object of

rewarding

The best part of being a tattooist is when someone comes in with a tattoo that is less than nice and you can fix that up or do something with it to make them happy with what they've got. I like that part a lot. Reworking some old crude piece of trash tattoo that they have gotten somewhere along the line and making it into something as nice as you can. That makes them happy and it makes me feel as if I've really accomplished something as far as helping the person out. Plus, you get a moment's glory because that particular customer thinks you are really a tremendous tattooist because you have made a silk purse out of a sow's ear

.jpg)